How can we inspire sustainable behavioural change?

It’s clear that information on its own is not enough to change behaviour. Behavioural science can allow us to understand how people process, respond to, and share information.

This can help us identify the drivers that transform simple awareness into climate action and daily sustainable habits.

Due to its potential, an increasing number of governments are also incorporating behavioural science into many aspects of their policymaking. Padraig Walsh, CEO of ChangeAble, runs a behavioural insights agency and explains the importance behind what his organisation does:

“What we want to do is use the incredible insights from psychology and behavioural science and apply them to make the world a better place.

So many societies' issues such as climate change, health issues, well-being & conflict emerge from human behaviour errors, and we want to disseminate this science and make it relevant in various sectors.”

When asked about the role of behavioural science in driving sustainability, Padraig explains what they often find is there’s a difference between our intentions and our actions.

He shares that policy often focuses on targeting individual motivations and trying to motivate individuals to change when, in fact, people are already motivated and want to be more climate-conscious in their behaviour.

Still, the systems and environments are limiting their capabilities and opportunities for change.

He gives some examples:

“We see this when it comes to financial limitations with the cost of retrofitting or electric cars, educational/skill deficits when wanting to switch to a reduced meat diet, or not having the cooking skills, knowledge, or confidence to change.

We even see opportunities in physical environments that limit the likes of cycling due to safety fears or perceptions of rainfall.”

“We want to see behavioural science used for good both in terms of making decisions that are good for society as a whole but also data-based decisions that lead to lasting and robust meaningful behaviour changes.”

Padraig proposes an alternative approach, moving away from focusing solely on individual actions.

He explains: “It’s what we call the I-frame (individual) in behavioural science, but more of our work is becoming conscious of the S-frame (systems).

Behavioural insights can help us design human-centred systems in our environments such as at home, in the workplace, in towns and in society that make climate action easier, more attractive, and the default option.”

He adds: “Our knowledge of human decision-making can help us to design these optimal environments for sustainability by making sustainable choices simpler, more accessible and habitual.

However, we first need to understand that framing matters; humans are more likely to change behaviour when challenges are framed positively rather than negatively. How we communicate about climate change and sustainability influences how we respond.”

Padraig explains further:

“Individuals are more likely to feel empowered to act regarding a positive frame such as ‘clean energy will save X number of lives rather than ‘we’re going to go extinct due to climate change’.”

The second sentiment might evoke an emotional response of hopelessness or anxiety and likely won’t lead to effective behaviour change.

Padraig believes we need to take steps informed by science rather than politics or creed.

Since climate change has been looked at as a behavioural concern, we have been able to instil hope in people and motivate them to take action.

However, he feels this has only been possible due to scientific evidence as the basis and not blind politically motivated actions and promises.

He adds: “Addressing the intention-action gap is an important consideration to take into account. Individuals in Ireland are informed about climate change and seldom doubt its existence.

They want to take action but may be confused about the ‘how’. Therefore, the mental load on people can be lessened by having changes on a systemic level and making climate actions easier for us mentally.”

Padraig attests that this can be achieved by using social norms to our benefit. We compare ourselves with those we think are similar to us.

For instance, we may compare our energy consumption to that of our neighbours, and a simple statement on our power consumption bills, starting with how we did compared to our vicinity, can be a powerful motivator for communities to become more conscious of energy consumption.

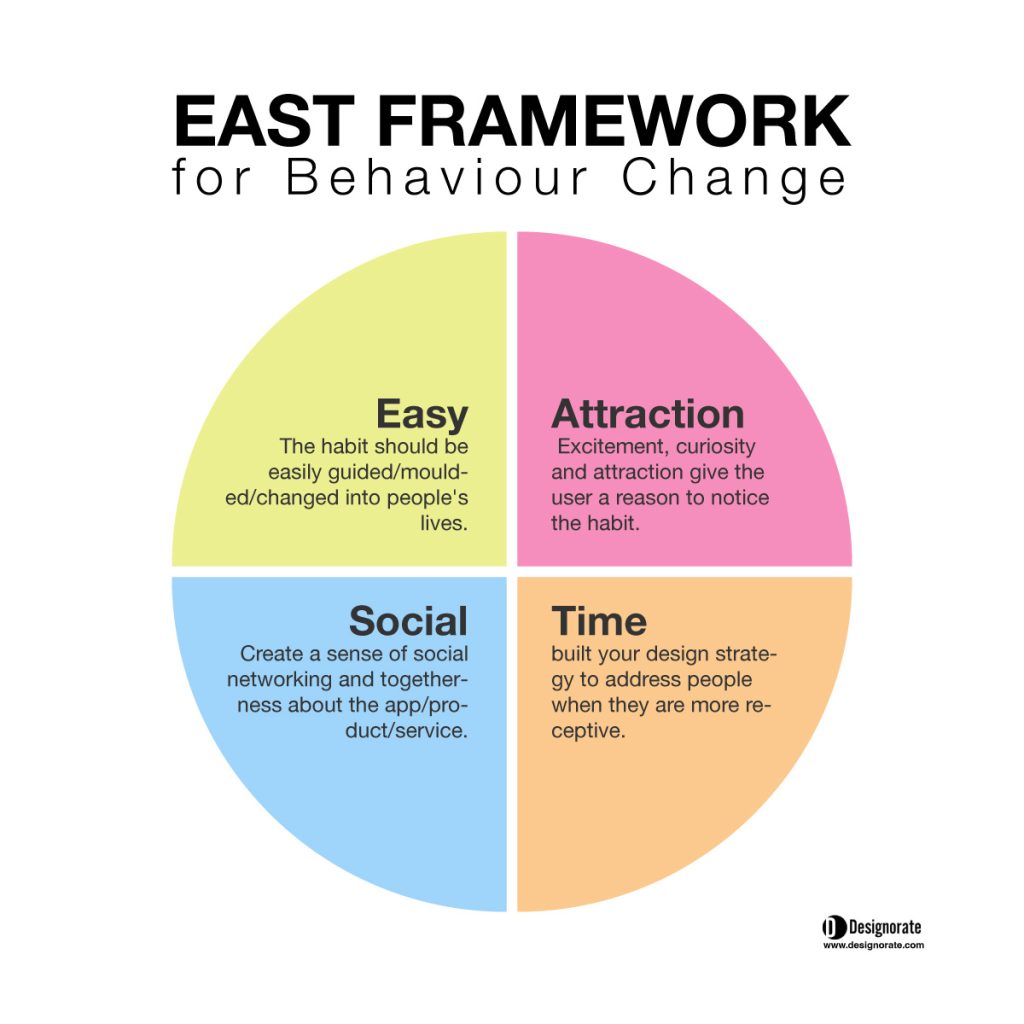

Padraig shares that his favourite behavioural science model for sustainability is the EAST model.

He says: “It is a powerful and simple framework to think about designing for behaviour change, and it’s particularly relevant to sustainability.

Our goal when promoting behaviour change is to make the desired behaviour - Easy, Attractive, Social and Timely.”

For example, we may be able to increase the cycling population if it was made easier to get access to cycling routes or if people had ease of access to bike-sharing schemes.

We can make sustainable meals more attractive in their appearance and description.

For instance, we could say ‘delicious creamy pasta’ instead of ‘vegetarian’ or ‘meat-free’. Emphasis on people’s social identity for a message to appeal to them can result in more initiative.

Padraig shares: “Using competition within and in between groups for sustainable goals can promote actionable change.

These techniques, coupled with a timely implementation, can make all the difference.

We can provide first-year students tips to shop sustainably or provide interest-free loans to students to buy public transport passes.

Adopting the EAST model can be highly beneficial once done with due consideration.

He says: “We are habituated to living a certain way, consuming a certain amount of goods or having a particular mode of transportation.

This requires systems-level change and effective policy as much as it requires individual willpower and motivation. Combined, however, behavioural insights and human/planet-centred design offer us hope that change is possible.”

Headline image by vecstock on Freepik